Half Day Rafting

One Day Rafting

Family Rafting

Rafting Weekend

History of the

Rouge River

The source of the Rouge River can be found in Lac Rouge, near Maison-Pierre, due east of the Rouge-Mattawin Wildlife Reserve. It flows down a 185-kilometer stretch of the Laurentian Mountains, and steers its way to the mouth of the Ottawa River near Grenville-sur-la-Rouge, Quebec.

When the last glaciers melted, the Ottawa River was the main drainage channel for the Great Lakes, until the surrounding topography created a natural, raised plateau in the landscape. A new canal was borne, connecting the Ottawa River to the St. Lawrence.

As it winds its way to the ocean, the Ottawa River leaves behind a fine clay sediment, creating long parcels of fertile soil in the middle of the tenacious Canadian Shield. Here, the Rouge River and the Seven Sisters Falls cascade down to join it.

The Ottawa River forms a natural border between the provinces of Quebec and Ontario, but the division is more than just geographical: its southern flank is home to rich agricultural land, while the north gives way to the Laurentian forests.

The Rouge River was known as the River of the Great Spirit

For several hundred years, the Ottawa River and its tributaries were the primary transportation route for the fur trade and exploring the western frontier. The huge beach at the Rouge’s basin was also used as a natural campsite for the Voyageurs and Amerindians.

At first, the Algonquin people controlled a large swath of the Ottawa River and its tributaries. At the time, the Rouge was known as the River of the Great Spirit, in honour of the supreme Chief “Gitche Manitou”.

According to the traditional philosophy of the Algonquin people, Manitou represented the power that resided in all natural things, encompassing their weak and strong qualities and both good and bad influences.

Samuel de Champlain was probably the first to attribute the name Algonquin to this specific group of Amerindians during his visit in 1603. In the tribe’s language, this meant “real men, mainly hunters”. The French then settled an agreement and created an alliance with the Algonquin and Huron people to acquire a portion of the control over the fur trade. As of this moment, they took control of all the traffic in the Ottawa Valley and the River’s tributaries. Étienne Brûlé was likely the first European to spot the Rouge, when he reached the Ottawa River in 1610.

Steven Bevin, a former employee of the Hudson’s Bay Company, built a trade post at the base of the River to help bolster business in the Rouge River Valley. Having previously worked for another trade post, he had acquired some of the Aboriginals’ language, which gave him a distinct advantage. Above all, this strategic position on the Rouge allowed him to intercept the Aboriginals before anyone else could, providing a significant advantage and negotiating power.

Étienne Brûlé was likely the first European to spot the Rouge River

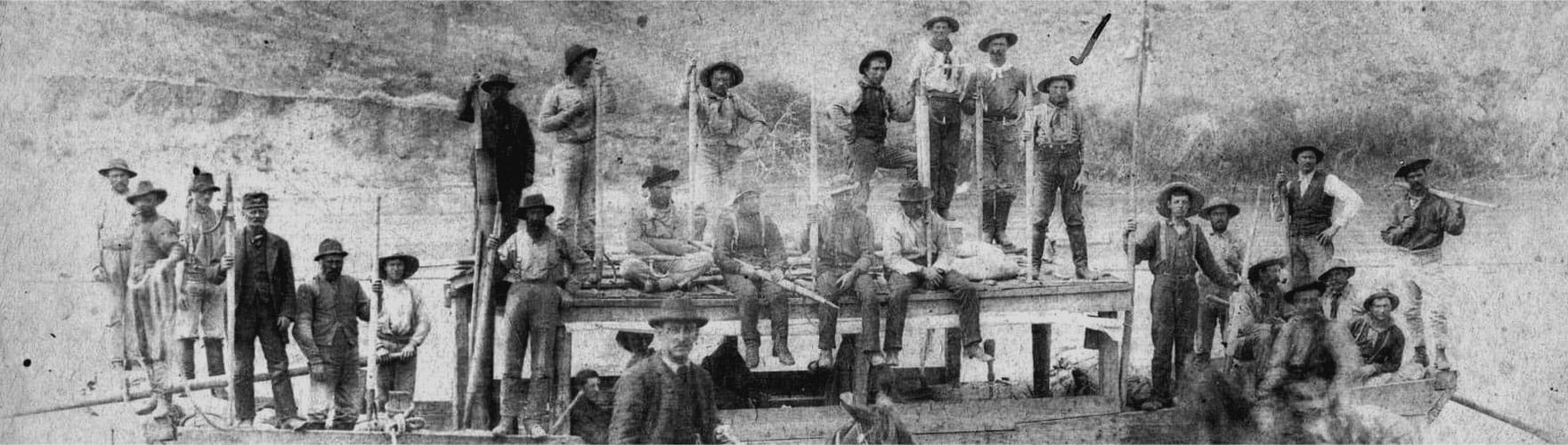

From the Rouge basin, large logging rafts flowed down the rapids all the way to Quebec City

The timber trade brought big changes to the Rouge River Valley. Founded in response to European demand, this led to further exploration, immigration and investment, along with a growing economy. In 1798, the City of Hawkesbury was founded and Thomas Mears built the first wheat mill there along with the first steamboat some time later.

The Union des bucherons de la Rouge, Gatineau and the Rideau River kept the mill running. The logging trade was always driven by specific needs and quality standards and relocated from St. John to the Rouge when contractors began scouring the deciduous forests for oaks and white pines. The balk-timber industry developed quickly in response to enormous demand from Great Britain, a country that was at war with Napoleonic France and had blockaded access to the Baltic forests in 1807. In 1812, the Hamilton Brothers, who were lumberjacks and businessmen and had previously been involved in the Baltic timber trade, seized the mill in Hawkesbury that they had helped finance. They went on to launch one of the most successful commercial lumber operations in Upper Canada. They obtained contracts from the Admiralty, which held the rights to cut on public land up to the Rouge and other tributaries. In fact, a large part of the lumber industry remained illegal until 1826. It was commonplace for lumberjacks to disrupt operations and intimidate both official governments and the competition. The Hamiltons played an active role in this violence through their efforts to maintain and develop their commercial activities.

However, in the mid-1820s, they began vying for government regulation to bring order to the business and guarantee the rights of big operations such as theirs. As such, pulpwood began flowing down the Rouge even before the fur trade had slowed. From the Rouge basin, large logging rafts flowed down the rapids all the way to Quebec City, where they were loaded onto ships destined for Liverpool. In 1830, British demand for pine in the Ottawa River drainage basin had become so great that it began to dominate the Canadian economy. Armies of men living in their barracks for the winter would emerge in the spring and float back down to civilization on their rafts. After 1850, Britain’s demand for balk wood began to tail off, but the American market picked up in its stead.